Speaker 1 (00:03):

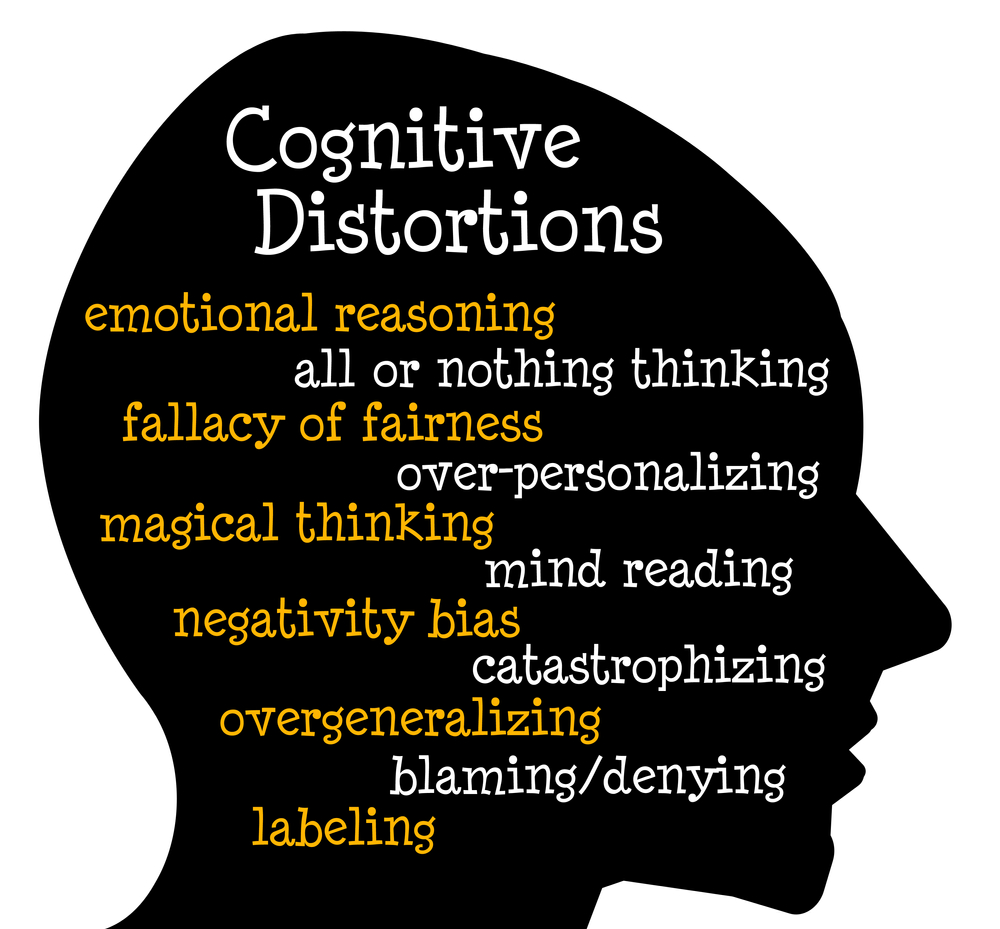

Welcome back to the renewal session. So last week, Katie and I, um, at the end of our podcast, decided that she was going to be in charge today. And I think she picked something like cognitive dissidents, but actually she landed on cognitive distortions and 10 forms of cognitive distortions. So I’m going to pass things over to her cause she’s going to take the lead. Cause if you guys didn’t catch that at the end of it, she, she wanted to get away with just naming the category and me doing all the prep. But I said, no, if you’re in charge, you have to do the whole thing. How’d that go, Kate?

Speaker 2 (00:46):

Okay. So this is just a lot of fresh pressure, but I also need everybody to be aware that my mom still did all the work. I’m just presenting it. So she’s just humble. I’m just presenting it. But anyway, um, hi everybody. I’m Katie I’m Marianne’s daughter and, well, I don’t know. I feel like there are people that jumped in in the middle, you know, and like, I

Speaker 1 (01:11):

Guess, so that’s

Speaker 2 (01:12):

True. Don’t, don’t go all the way to the first episode, I guess I feel like, you know, it’s nice to have a little refresher of who this random voices, but I’m Katie I’m Marianne’s daughter. I was also a therapist at one point in time. Now I work in a hospital, whatever. So I love cognitive distortions because it was a thing that I taught a lot when I used to lead groups at a behavioral health hospital. And what I thought was so interesting about it is it’s such a cool tool to be able to identify things and like patterns of thinking that we don’t always identify. Like we don’t always have words for whatever it is that’s going on. So, um, mom found this awesome resource from David Burns who actually wrote the feeling good handbook, which if you haven’t read that, I actually own a copy of it. I haven’t opened it, but I’ve heard it’s very good. Um,

Speaker 2 (02:06):

I was really, I was really trying to build my book collection and then I got halfway through all the books I wanted to buy and I realized I’m not a reader. So I had like a, I had an identity moment in the middle of may and building my therapy book collection. So anyway, there’s pamphlet came out, which that’s three pages, which is totally fine. I can handle that. So we’re going to talk about cognitive distortions and I’m just inviting you to think about, because it’s really easy to identify other people’s distortions. You know, like I can pick out 10 things that mom has wrong and like all of her distortions, but it’s really important to reflect internally people about what the distortions are that you feel like you struggle with.

Speaker 1 (02:52):

Oh my gosh. But as we’re going through this, are you going to out me?

Speaker 2 (02:57):

No, I’m going to try and just out myself, but a lot of my flaws are a result of as a result of you. So just kidding. I’m just kidding. I’m just feeling feisty today, whatever.

Speaker 1 (03:12):

Anyway.

Speaker 2 (03:13):

All right. So, okay. So the first one, which I think a lot of people can identify is all or nothing thinking. So in itself that is a distortion, right? Because we can, we can all probably agree that when you think an all or nothing terms, like for instance, if I failed a math test, that means I’m bad at math, not just I had a one-off experience, right? So it’s either an all good and every test or I’m all bad period. And so

Speaker 1 (03:43):

Actually, even though that’s all or nothing thinking, I feel like that might be true.

Speaker 2 (03:48):

Well, I mean, yes, a lot of people are bad at math, so that is some personal inventory of

Speaker 1 (03:56):

I’m going to make it about all other people. You know, you’re bad at math. What’s nine times six.

Speaker 2 (04:03):

I’m just, I can’t live without a calculator, but whatever. Anyway, so all or nothing thinking tends to be very black and white. It tends to eliminate any possibility for the in-between feelings of, you know, oh, I can feel partially about this. And I feel partially about that either. I feel passionately about one or the other. There’s no, both. And in these situations. And so in, in itself that distorts our thinking of poor perception of reality, because we’re not allowing room for that in between. Um, which is the space where we find grace and we find, you know, development and like complex thinking is in that, in between. And so something to keep in mind, if you’re looking at,

Speaker 1 (04:47):

Just to add to this, that all are all or nothing thinking actually can also be, trauma-based thinking it’s not always, it’s not always trauma based thinking, but there is an element of all or nothing thinking that comes with trauma.

Speaker 2 (05:04):

Totally. Yeah. Yep. That’s so true. Yeah. And I think a lot of people it’s feels safe to look at things through all or nothing thinking because really it’s either all or it’s nothing. And so you only have two options, right? So it’s a lot less confusing. But the problem with that is that you are distorting all of these in-between options that could provide you safety and time to make decisions and things like that. I will out myself. I tend to be an all or nothing thinker. And so I tend to make decisions very rapidly and very quickly just out of fear. And so it’s better for me when someone tells me you’re being an all or nothing thinker, because it allows me the opportunity to sit back and think about that in between area, if that makes sense, which kind of

Speaker 1 (05:57):

Leads into the next one that, um, we experienced sometimes together, uh, is the overgeneralization, right? So it’s the, it’s the always and the never of and fine. And sometimes he can, these can go hand in hand, but a lot of times it’s usually the thing I see it most in, in my life is either in an argument or in like the telling of a story. So like, if I’m going to tell a story to you, I’d be like, oh my gosh, he always does.dot dot, right. Or your brother never does dot, dot, dot, whatever it might be. So a lot of times in stories, I will use that as a form of expressing frustration. Like I’m exasperated with the person in a set of circumstances, I feel like it’s never going to change. And so everything goes to this extreme comes like, you know, this, this sense of always never in a man I’m telling you that backfires every overgeneralization,

Speaker 2 (07:12):

Well,

Speaker 1 (07:15):

Cause price locked in on that one phrase like always or never. And I’m like, okay, fine. Four times you did it. Right.

Speaker 2 (07:26):

Well, and that’s the thing that’s tricky about it too, is sometimes it’s subconsciously building a narrative for ourselves that feels very limiting. And so even if we want to break that general over station, it can feel so huge because we’ve made that statement of I never, or I don’t like for me, for example, because I think a lot of people can relate to like, you know, oh, I’m not a good exerciser, right. Or whatever. But just another example is like, I strive to be an artist. Like I hold that term in high esteem. Like I think people that are artsy and people that are creative are like, they just blow my mind. And I have always said, oh, I’m not really an artist, but it was because I hadn’t found my medium. Right. And so I’m not a painter that is true, but I can be an artist and use art in other ways. So it’s important to, it’s important to identify, like if you’re saying, oh, I’m not good at taking care of my personal health. Well, what does that mean? Does that mean you don’t like long walks on like around your neighborhood? Well then that’s fine, but you can do other things. Right. So don’t allow that to become an overgeneralization. Cause it can be very limiting and it builds a narrative that’s not entirely true,

Speaker 1 (08:42):

Which narratives rule our lives. Right. Like, I mean yeah. In a story in your mind and really quickly, it can take on a sense of truth. If you tell it long enough to yourself, I think it’s illusionary, illusionary truth something. Right. So the other one that kind of is the third one of

Speaker 2 (09:07):

Mental filter, right? Yeah, yeah.

Speaker 1 (09:09):

Yeah. So this is the idea that there could be 20 positive things that are said, but you catch that one negative and you end up kind of overthinking that one negative thing. Um, and it can really taint a whole experience. I’ve had this happen where actually it’s not even that a negative comment gets made, but rather it’s like the lack of any comments. So I could be doing something like, I’ll give you an example. So the very first time I ever spoke in front of a group of people, um, a couple of my closest friends were in the room and the whole time everybody else is like shaking their head, like, yeah, this is good. You know, you could see people writing down and whatever, and then it comes to a close and people come up and they’re like, oh, you’re really good. Thank you for doing that. You know, I, this was my takeaway, right. So we leave and everything. And I go about my life. I’m chatting with my friends, you know, within the course of the next week, they never mentioned the talk. What I know. And I literally was like, oh my God, they must have thought I socked because

Speaker 1 (10:33):

I know, I know. But the thing of it is, is like, I, I, um, their site truthfully, I think they just were like, oh yeah, she of course already knows. She’s good. And we’re here for whatever she does. And we love her, but in my mind, because they didn’t send me like warm, fuzzy affirmation. I was like, oh, maybe I actually sucked. And they’re just not going to tell me. Right. So I filter things through that. Sometimes a narrative that gets picked up in your childhood of like, you’re so dumb or she’s just the, she’s just the, the stupid one in the family, that narrative, we become to filter everything through these negative messages that we pick up in children as children.

Speaker 2 (11:24):

But even like, I know people that have been labeled as like the funny one and their family. Right. And so they’re like, they, they over-generalize themselves as though I’m the funny one. And then when things aren’t funny, they don’t know how to like interact with their family. Right. They don’t know how to get through serious situations. And so they feel like they have to overcompensate. Right. Which, you know, so I think it’s just challenging because I think it’s a thing that happens so regularly, but it can be really, you know, it’s important to acknowledge other character traits instead of just choosing that one filter thing.

Speaker 1 (12:02):

Right. Right. And along and along with that is this discounting of the positive. That’s another common thing that we do is we just discount the positive and kind of take out any, any joy that might be in that set of circumstances. And instead focus in on how unrewarding or an adequate and inadequate or how it didn’t measure up to what we were expecting to do and experience. And so it’s like, okay, yeah, that was good. But it was whatever, you know, like we just are going to ignore it then another one. So you can tackle this one is jumping to conclusions.

Speaker 2 (12:46):

Right.

Speaker 1 (12:47):

I feel like this is a fan favorite for our family, but it’s like either mind reading or fortune telling is kind of the two breakdowns of those. So you can talk about that real quick.

Speaker 2 (13:01):

So I think mind reading kind of, I think that is self-explanatory, it’s this idea that like, you know, you have an interaction with someone, right. I’m starting

Speaker 1 (13:16):

To have a park,

Speaker 2 (13:17):

Right. Without even really checking,

Speaker 1 (13:20):

Huh? You were cutting out. Say it again.

Speaker 2 (13:23):

Oh, sorry. It’s this idea that like, you know, you have an interaction with someone and you leave the interaction and you start thinking, oh, I just know that they don’t like me. Right. Without actually ever checking with them how they feel about you or, um, uh, another thing that happens in relationships a lot is when you get to know someone really well, you believe, oh, I can predict what their reaction is going to be. Or I can already tell you, he’s not going to do this. Or I can already tell you, she’s going to say no to that. Right. And so we start like limiting our interactions based off of our own interpretation of what we think is going to happen. Right. And we start to read people’s minds like that. The other one that we talked to, the other one that you mentioned is,

Speaker 1 (14:08):

Hold on, let me say something about that one too, because there are a lot of white people out there in the world and they get kind of, this happens to them a lot because they don’t express what they’re thinking. And so people will just make assumptions.

Speaker 2 (14:28):

Yeah.

Speaker 1 (14:31):

Yeah. And they fill out, fill out the whole thing. I was talking to somebody the other day and they’re, they’re just by nature, a listener. And so what has happened is people have started to read her face. Right. And so she’ll be sitting there and she has to be so aware of what her face is doing because people interpret her facial expressions.

Speaker 2 (15:01):

That’s a bad, that’s a bad time to have expressive eyebrows.

Speaker 1 (15:05):

Oh my gosh. How about that girl? Okay. Just on a totally excited note, you

Speaker 2 (15:08):

Know, Emilia Clarke. Oh,

Speaker 1 (15:10):

Amelia Clark.

Speaker 2 (15:12):

I knew you were going to talk about her. Emilia Clarke has the craziest eyebrows. I love her, but her eyebrows are so distracting, but you know what

Speaker 1 (15:20):

They learned, they weren’t in game of

Speaker 2 (15:22):

Thrones. No, it was just in that movie that

Speaker 1 (15:25):

She was in. What was that? You before me or

Speaker 2 (15:28):

Meet me before you are this guy. And he was like her, she was her character, his caretaker

Speaker 1 (15:34):

Eyebrows were all over the

Speaker 2 (15:35):

Place in that movie. How about, how about her shoes in that movie? Her shoes were incredible. I read an article about them. Oh, he did? Oh yeah. They’re like super quirky. You should check it out anyway. But yes. Well, and that’s so funny that you say that because a lot of people with the, with the pandemic and whatever, like are so used to their masks. Right. And so like, you know, your facial expression is half hidden because of your mask, you know? And so like you could be hating on somebody and somebody wouldn’t know, you know, or

Speaker 1 (16:07):

You might not be hating on anybody, but they’re assuming you are.

Speaker 2 (16:11):

Right.

Speaker 1 (16:12):

Because they’ve gotten used to reading your face anyway. Okay. So go on to fortune telling,

Speaker 2 (16:17):

Okay. So I am a culprit of fortune telling I am. I that’s my favorite probably cognitive distortion, even though I don’t think you should have a favorite, but I tend to do this a lot. So for telling us this like concepts,

Speaker 1 (16:30):

I’m gonna disagree. The next one is your problem. But go ahead. We’ll go with,

Speaker 2 (16:34):

Okay. I got all of them people. Oh, I was funny. Cause I was talking to a friend about this at work and I was telling her about it. And she said, I was going down the list. She’s like, I’ve got that. I’ve got that. I’ve got that too. And I’m like, it’s not things that you’ve got. It’s like, it’s like everybody does

Speaker 1 (16:55):

Out of infectious disease. I

Speaker 2 (16:57):

Was like, she’s a hypochondriac for the cognitive distortions. But anyway, she’s very distorted if she’s listening. She’s very distorted anyway. So anyway, okay. So fortune telling is that you predict that things will turn out badly before you like actually have evidence for that. Right. So like you would say, oh, I’m not gonna apply for that job because I know I’m not going to get it or I’m not going to, you know, invite that person over for dinner. Cause I just know that they’re going to say now. Right. And so, so you just, you start to predict things are going to end poorly before you even like take the shot. If that makes sense. Yes. Yeah. And I do that. I do that with not with people necessarily, but I do do that with like, um, like life goals. Sometimes we’re all convinced myself like, oh, it’s not going to go the way I want to. Therefore I’m just gonna, you know, I don’t want to face the rejection. And so I’m just going to protect myself. And I think a lot of people do it as a form of protection, you know? Like, oh, I don’t want to get my feelings hurt. Therefore I’m just not going to try.

Speaker 1 (18:06):

Yeah. And I think that’s like, you know, kind of coincides with limiting beliefs. I think the other form of fortune telling is the predicting of what another person’s going to do.

Speaker 2 (18:20):

What’s that migrating. Yeah. Yeah.

Speaker 1 (18:22):

It’s well, I think mind reading is assigning like a thought to a person. Whereas fortune telling, I think is predicting what they’re going to do. So for instance, let’s say I’m talking to you about something like, I know here’s a good one. So, so I wish you guys could see us. We should sometime just upload our video of this because half of reactions are in her face before they’re in her, like before she sends anything, like, I’m going to predict that you’re going to roll your eyes. When I say this, all you have to do is tell the audience whether or not you rolled your eyes. Okay. Did you vacuum?

Speaker 2 (19:09):

I did vacuum. No eyeball. No. Eye-roll asked me the other question though. Go ahead.

Speaker 1 (19:17):

Did you shampoo the carpets?

Speaker 2 (19:19):

I did not. Nor did I dust and I told you I dusted. I did not.

Speaker 1 (19:31):

Did I not say that last night? I go do not lie to me. We both know you didn’t does.

Speaker 2 (19:35):

And I said, I’m not lying. I dust it. And I was lying

Speaker 1 (19:40):

Anyways.

Speaker 2 (19:41):

There’s shame. There’s shame the mice.

Speaker 1 (19:49):

Is that what you’re saying? You felt dusting. Shame.

Speaker 2 (19:54):

Yeah, I did.

Speaker 1 (19:56):

All right. So here we go right into the next one. Magnification. This is when you exaggerate the importance of your problems or your shortcomings, right?

Speaker 2 (20:05):

Oh yeah. That is my favorite.

Speaker 1 (20:07):

Yeah. This, this is like, I would actually say it’s a genetic trait in our family to be exaggerated.

Speaker 2 (20:14):

Oh my gosh. Can I tell them about the Vernon? Yes, please. Okay. So

Speaker 1 (20:20):

I think, I think it’s a

Speaker 2 (20:21):

Grainy thing. Okay. So it’s a greedy thing. People listen up. Okay. So when I was little, I learned very young that if there’s any family drama and we’re out in a place where no one knows us, somehow when we’re talking about our family drama, we get five times louder and make it 10 times more exaggerated just for the shock of it. Right? And so we’ll be talking, I have a vivid memory of when we were at Kohl’s I was like six or something. My granny and mom loved, well, granny loves Kohl’s. She’s mad at them now because they messed up her Kohl’s cash or whatever. But anyway, so we were at Kohl’s and I have this vivid memory of like, something was going on with Christmas. There was like some drama about Christmas and we were out shopping and mom goes, can you ball right there?

Speaker 1 (21:20):

I did

Speaker 2 (21:20):

That. Yeah, you did. And then granny was like, I just can’t even believe that that’s the most ridiculous thing I’ve ever heard in my whole life. And it was like this whole thing. And it was like, they weren’t actually mad. They were just talking, but it was like the shock of it. So it was like this. Yeah. So we call it like, tell him, tell the story like granny does. It gets very long with a lot of details that shouldn’t probably be there or, or aren’t real. That’s very loud. But anyway, so if you ever hear us doing that, that’s, we’ve been trained well, but anyways, so yeah, the magnification thing is definitely, I struggle with that. I make little mountains out of molehills a lot, but I think it’s, I think it’s just a way of saying, like, I think that we’ve talked about this before.

Speaker 2 (22:13):

I don’t know if it was on the podcast or if it was in book club, which check it out next time mom has a book club. You should join book clubs. But anyway, we talked about this before. We’re like women, I think will minimize stories. Right. And they’ll make it seem like, oh, I don’t have any issues, but then sometimes we’ll do this magnification thing. And I think sometimes it’s just a way to like tell people that you’re struggling with that without actually asking for help, you know, just like hoping that they kick in and say, Hey, let me help you. Um, and so I think some of the, sometimes I, I just start things in my own head for fear of feeling weak. If that makes sense, like I magnify the issues or you’re in,

Speaker 1 (22:56):

You’re really in pain and you are, you’re struggling to reach out to somebody and say, I’m really in pain. So you magnify the intensity of what you’re saying, because it doesn’t seem like it’s big enough if you don’t make it a bigger deal.

Speaker 2 (23:12):

Yeah. Right.

Speaker 1 (23:14):

Okay. So give me, we got 7, 8, 9, and 10. So we got a hustle.

Speaker 2 (23:20):

Okay. So emotional reasoning. I feel like this is the, this is the seventh one. Emotional reasoning is if you know, do you ever have a situation where you’re just like, I just really don’t want to, therefore I’m not going to, even though it’s detrimental to your success,

Speaker 1 (23:37):

You’re asking me if I ever have that. Right. Like, I don’t know, give me an example.

Speaker 2 (23:42):

Like, I really don’t want to go get my oil changed, so I’m not going to go get my oil changed. Okay. So my car could die. Like you need to go change. Right. But I, I hate sitting in the line to get my oil change. Therefore I’m just not going to do it. Right. So I use the emotion of, oh my gosh, the boredom and the, the like,

Speaker 1 (24:08):

Does that make sense? Yeah. Like it’s like, I don’t it’s I don’t want to write. Right. You’re going to assume, I think it’s like actually defined as you assume that your negative emotions actually reflect the way things are. So I feel terrified about going on airplanes right before it must be dangerous to fly.

Speaker 2 (24:31):

Yeah. That’s a better, that’s a better example. Yeah. Right.

Speaker 1 (24:34):

Or I, I feel guilty. I must be a rotten person. Right. So, oh, really quickly. I was talking to somebody today, yesterday. So just for the audience yesterday, Katie had, um, one of the professors from covenant seminary speaking at her church and she called,

Speaker 2 (24:55):

Which is, which is crazy because mom went to covenant. I live in Memphis and covenant is in St. Louis. So he had come down from cabinet to speak at my church.

Speaker 1 (25:04):

Right. And he talked about, um, the difference between true guilt and vague guilt.

Speaker 2 (25:11):

Yeah. It was really good. It was good. Basically. Basically what he said was that God does not do vague guilt. Right? Like if, if your guilt is going to be from God, it’s going to be very specific and you’re going to know what the sin was. And so that God can offer you the opportunity to repent specifically for that, that guilt. Right. Whereas Satan does vague guilt. So he will do vague guilt with no specific thing to be guilty for. And he will disguise himself as like, well, he’ll use it like pause and he’ll cause confusion and Christians, then they will doubt and they will be confused and they will struggle with that season. Whereas like, God doesn’t want you to struggle. God’s not a God of confusion. He’s going to let you know, you messed up repent. Right. Right.

Speaker 1 (26:10):

And, and, but Satan wants to confuse you and actually caused you to believe that God is angry with you even.

Speaker 2 (26:19):

Yeah. I just thought that was so freeing. I thought that was so freeing to know, because I think there’s so many seasons in life where people are just like, man, I just feel really guilty about what’s going on. Or I feel really like, I’m like, I messed up, but I can’t really see. I don’t really know why I feel like that. I just feel like that. And it’s really powerful. I think, to bring in this idea that that could be Satan like that be, you know, your mind getting twisted to cause confusion. So I thought that that was really

Speaker 1 (26:51):

Which again, we’re doing good on the lead-ins right. The little segues, because the next one is should statements. I feel like everybody does this. Right. It’s like I should have done. And it’s directed at yourself and it’s usually leads to guilt and frustration. So like should statements that are directed at other people, so tend to lead to anger and frustration. So let me say that again, statement, like if I, if I’m talking about me, I should have done X, Y, Z. That’s going to lead me to feel a sense of guilt or frustration. But if I’m saying Katie showed up, it generally is leading to anger and frustration in me, towards you. Right. Right. So I think when I, when I realized like, wow, okay. I, I use should to blame myself. Right. Right. And I use should, because I stuck it on you. And because I’m really angry of you not meeting my expectations. Right. But I think a lot of people try to use should statements to should, or shouldn’t statements to motivate themselves. And I always say this it’s like one of my mantras, if ever, if ever somebody tried to accumulate my mantras, this would be on it. Oh wait. You and your brother did that one time. Didn’t you, you made a nasty little list of all the things I say multiple times. But yeah.

Speaker 2 (28:23):

So one day when mom tells her testimony on here in the middle, I’ll hop on and be like, listen, people, this is what, this kind of stuff she used to say. As advice you’ve gotten, it’s gotten a lot better. Like she used to say stuff rather than like, maybe we should say like, okay, here’s an example I love to shop. And she would say to me, now she would say to me, I just really want you to think about if you’re trying to appease your, if you’re trying to soothe your emotions by buying that item. Right. So that’s what she would say. Now she used to say to me, you need that. Like, you need a hole in your head Or Jack would come in from the playground. And she say, oh, you smell like the good earth.

Speaker 1 (29:10):

I got that one from granny though. Or like, know like a goat.

Speaker 2 (29:14):

Yeah. You smell like a goat was another good one.

Speaker 1 (29:17):

Hey Jack, why don’t you go to take a bath before we have dinner?

Speaker 2 (29:22):

Right. It’d be like, you smell like Lord Jesus. You know,

Speaker 1 (29:26):

You know, he came into the kitchen the other day. He’s gone now, but he came into the kitchen the other day and we’re like, oh, we’re just going to miss you so much. When you’re gone. He went in for a hug and I was like, oh my God,

Speaker 2 (29:42):

There’s something different about that. Twenty-something year old, boy.

Speaker 1 (29:48):

It gets bad when they’re young too though. Okay. So now we’ve got labeling.

Speaker 2 (29:53):

Okay. So this one, I feel like a lot of people do when it comes to like other people. I think people are really good at like labeling other people. So let’s say for instance, somebody does something and it hurts your feelings, right? Oh, she’s such a jerk. Right. Rather than taking into context, all of the things that are going on in his life outside of that one action. Right. And so we do that also with ourselves. Right. I used to do that a lot. I’ve gotten better, but I used to do that a lot when it comes to, for instance, I’m, self-conscious about my hair. I don’t know why it’s just very fine, whatever. And I would say, I just have bad hair. Like I just have bad hair, but what was actually happening was I’m not great at I wasn’t great at styling it. Right. And I couldn’t figure out how to get it to look like I wanted to. So instead of saying, I just need to practice more. I would just say, no, I’m not good at it. I have bad hair. And so I would label myself as a person that has bad hair or a person that doesn’t like to exercise or a person that’s not artistic when there’s all these other things going into it. Right. Does that make sense?

Speaker 1 (31:10):

Yes, totally. And I think sometimes like we can do it almost worse than we do it with others, but we just call it self self-deprecation. Yeah. Whereas it’s more clear when it’s somebody else that you’re laid back. Right? Yeah. Because if I was to say it about myself, like, oh my gosh, I just have such bad hair or I just never look cute in anything. Or, I mean, you name it, whatever it is. I’m so like, I’m so stupid, you know, to me it can be, that’s just self-deprecating. But in reality it really is. I’ve just decided to label myself as something which then ends up cultivating these limiting beliefs, this all, or nothing thinking. Cause I do think that labeling can be an extreme form of all or nothing thinking. Um, I th I, you know, this is a common thing, like, cause I know they’re never going to listen to the podcast. Ha ha. Grady likes to do this with pop. She likes to label Monitoring labels.

Speaker 2 (32:29):

Yeah. She’s got some pretty, she’s got some pretty flamboyant, uh, some pretty flamboyant labels for them.

Speaker 1 (32:34):

So what’s the why behind her labeling. And it really is just a joke when she says it, you know, like it’s not like she’s really trying to be hurtful. She’ll just, you know, that’s just her way of blowing off a situation sometimes. Oh, what are you going to do? He’s just, you know, a difficult person or whatever. But I think sometimes we do labels also because we’re feeling a sense of anger and frustration and we, and we don’t have much room to fit creatively to explain what we’re saying. So it’s just faster to throw a label on it, then explain like the details of why I perceive that person in that way. Like, oh, he’s such a jerk is so much easier than to tell the whole big, long story. Right. Right. Which is like, even with you with your hair, like you were like, okay, I just have bad hair.

Speaker 1 (33:25):

It’s easier than saying my hair is fine. And you know, I’ve tried lots of different products and it just never seems to work out. Right. You just go to a lot more time, a lot more time. So we just throw a label on it cause it’s faster. And we all kind of go, oh, you know what bad hair means. Right. And put this out as we don’t always know what bad hair means. Right. Yeah. Or whatever. Okay. So the fo the 10th and final one is personalization and bullying. So personally I feel like honestly could be two separate ones, but for the sake of even numbers, we’re going to keep them together. Okay. So I’m just gonna, gonna succinctly try to say this, that like personalization occurs when you hold yourself personally responsible for an event that isn’t entirely under, like without your control, does that make sense?

Speaker 1 (34:18):

Like, I’m going to, I’m going to take on the whole lion share of this. So an example of this would be, so you guys grew up in a Christian home and there were a lot of principles that we wanted you guys to, um, consider applying to your lives. Right. But the world has this way of pulling us into choices that, you know, we don’t always think have an impact. Okay. So let’s just use this as an example of like, let’s say you underage drink. Right. I found out about it. Right. I would turn it into, see, I’m a bad parent because you didn’t do X, Y, Z. Instead of me standing back and saying, wait, Katie has free, will free choice. And I raised her to be responsible and to not drink before she was 21 or whatever. But she chose that. That’s not a reflection on my parenting. That’s a reflection on her ability to make free choices, but personalization becomes like, it’s my fault. Right. Right. And then I think Barry, I think it’s very inter or I think that’s very easy to

Speaker 2 (35:37):

Do in the work setting also, because I think there’s a lot of times where we’re working on a group project and the group project goes south and we think, oh, like I could have done more. Right. Or I, you know, and that goes back to those should’ves also. But I think that that sometimes people blame themselves for things that are out of their control in the work setting as well.

Speaker 1 (35:59):

Right. But then the second side of that is the purse. So there’s one side, which is the person who says, it’s my responsibility. It’s all my fault. If I had done better, this wouldn’t have happened. Right. But then there’s the other person who can do the opposite, where they blame all their people for their circumstances and problems. And they overlook the ways they’ve contributed to the problem we call this, I call this when you and I are talking about it is abdicating responsibility. So the first one is overtaking the responsibility and the other under taking, right. So I’m abdicating my responsibility in the situation and blaming it on other people. But the problem with blame is it doesn’t usually work very well because other people will resent you for being, making them the scapegoat.

Speaker 2 (36:47):

Yeah. That’s

Speaker 1 (36:48):

True. And that goes into that whole boundaries issue. Right? So abdicating responsibility and blaming other people causes us to start distorting our thinking like, well, it’s not my fault. It’s not my fault that that happened when really actually, or fault.

Speaker 2 (37:08):

Right. So let me just ask this because I have a question about this. So this is a funny example. Wait,

Speaker 1 (37:16):

You asking me like, is this related to you and me? Are you just asking like a bra?

Speaker 2 (37:21):

No. It’s related to you and I’m going to out, you I’ve waited 10, I’ve waited 10 distortions to out you. So mom has this funny habit of when she does not want to go to something. She will use the stop

Speaker 1 (37:37):

Because people [inaudible]

Speaker 2 (37:49):

Okay. Oh my gosh, whatever. Never mind people. It’s fine.

Speaker 1 (37:59):

Your father has polio.

Speaker 2 (38:01):

So that’s the example is that when mom does not feel like she wants to go to something, somehow Papa always ends up sick magically. She will say, oh, Neil’s not feeling well. Oh, Neil’s leg is hurting. And so they’re running the running joke in our immediate family because none of her friends knew about it until now, but now you can off Kohler on it. Anyway, just you can start using Lulu. She’s all you can just say, we have to stay home. We’re not sure if she’s going to die soon or she’s like 17 years people. But anyway, but anyway, so the running joke is that Papa’s now got polio, tuberculosis cancer. He’s got these things wrong with it. That’s an example of passing blame onto someone else for your own emotion I had

Speaker 1 (38:56):

Seriously. I literally am going to think long and hard out you cause that bold on your part bowl.

Speaker 2 (39:08):

You can out me next time

Speaker 1 (39:10):

Checkmate. Oh my gosh. That is on real. Well, glad to hear that you are fully attuned to all of my foibles.

Speaker 2 (39:19):

Yeah.

Speaker 1 (39:21):

All right. We covered them. Maybe we should talk about how to, um, combat these things like strategies for changing this stuff.

Speaker 2 (39:31):

Yeah. That would

Speaker 1 (39:32):

Be really good. Probably do it. Cause I mean, every one of us can look through that list and say, I mean, I can’t, I just can’t even imagine that somebody would look at it and go, oh, I don’t do that. I mean, we live in a world where this stuff is so commonplace that, um, so even if you’re not externally demonstrating these distorted ways of viewing things they’re happening. So, you know, and I don’t even know that we necessarily think of them as problematic and maybe they’re not on the grand scale of life. Right. But if it, if what we understand that these lead to trickling issues like slippery slope into limiting beliefs, changing the narrative of your life, running, running people through this kind of thought process, when you develop relationships or you’re trying to interact and communicate with somebody like it can hinder you communicate or how you experience relationships with people.

Speaker 1 (40:32):

So, you know, it’s all funny. And we give a lot of, I think, um, humorous, practical examples, but it’s when this is done over a period of time that it begins to shape the lens at which we see things. And that’s when problems like distorted, right? And it’d be unhelpful to our success and fulfillment as an individual. So let’s come back next time and talk about the ways that we can strategize ourselves, how we catch it before it goes too far. And let me tell you, if anybody takes away anything after all the different times that we talk about things, it is that we should incorporate the circling back. I like firmly believe in the ability to go back and say, Hey my, Hey, my bad shouldn’t have done it this way. This is what I thought about. And here’s how I wish I had done it. And we can do that towards others, but we can do it towards ourselves where we give ourselves a little bit of a break and say, okay, I didn’t do that. Great. Yeah. I’m going to work to do that better. Right. Because now I know I know better, but, and that’s why even, I think you would agree that growing up when I did things that were, you know, unhelpful, traumatic, whatever, towards if I was aware of it, I would circle back.

Speaker 2 (41:56):

Absolutely. Every time

Speaker 1 (41:58):

I, I didn’t do that. Well, you know, and so I will confess that I have a tendency of using your father’s fake illnesses. Well, I will do better. I’m going to have to now. Cause every time I couldn’t find it somewhere, we’re going to know if I’m saying no, I can’t come. Oh, it’s probably because Neil’s sick. Yeah.

Speaker 2 (42:22):

Um, well it’ll definitely tell you, who’s listening to the podcast because if they don’t say anything about it, they didn’t hear it. So,

Speaker 1 (42:31):

You know, there are so many people that have just like randomly and I’m just like, what the heck?

Speaker 2 (42:37):

Weren’t we supposed to post something on Instagram last week?

Speaker 1 (42:42):

I feel like we make promises a lot and we don’t keep them one arm. What were we supposed to post? No. Which is why you’re asking me.

Speaker 2 (42:51):

Well, I feel like we were supposed to post something on Instagram, but the only thing I can think that we talked about was mattresses. So anybody want to see a picture of a mattress? Just let me know and we’ll set it up.

Speaker 1 (43:03):

Oh my gosh, that’s Stop now. Stop now while we, before we digress into all of these ridiculous things. So, all right. I love you. Go, go get your day on. I’m gonna let you go. I’ll see you at book club seven. O’clock

Speaker 2 (43:16):

Uh, the club. Alright, bye. Right. Bye. Bye.

PLEASE COMMENT BELOW